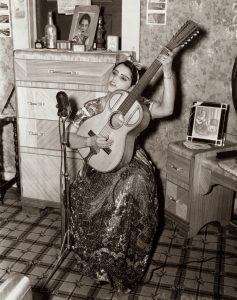

Lydia Mendoza and Her Acosta 12 String

Much of my appreciation of old instruments comes from listening to old recordings, seeing old photos of the musicians and asking the question, “What are they playing?” The harder the instrument is to identify the better (I especially appreciate instruments that were built in small shops). I then start digging and begin a process which a buddy calls “guitarcheology”, trying to find out as much as I possibly can about the instrument and the people who built it. I then put together the pieces of the puzzle and try my hand at building one. I have done quite a few projects like this and each time I gain a greater appreciation and understanding of the musicians and the luthiers who made their instruments. These projects have put me in touch with the families of the musicians and the makers and I have heard some wonderful stories. A year or so ago my friend Nikki Grossman asked me if I would be interested in making her a 12 string like Lydia Mendoza’s. I was very excited at the prospect of finding out more about Lydia and trying to find out more about the guitar she was playing in the iconic photos of her early career.

Much of my appreciation of old instruments comes from listening to old recordings, seeing old photos of the musicians and asking the question, “What are they playing?” The harder the instrument is to identify the better (I especially appreciate instruments that were built in small shops). I then start digging and begin a process which a buddy calls “guitarcheology”, trying to find out as much as I possibly can about the instrument and the people who built it. I then put together the pieces of the puzzle and try my hand at building one. I have done quite a few projects like this and each time I gain a greater appreciation and understanding of the musicians and the luthiers who made their instruments. These projects have put me in touch with the families of the musicians and the makers and I have heard some wonderful stories. A year or so ago my friend Nikki Grossman asked me if I would be interested in making her a 12 string like Lydia Mendoza’s. I was very excited at the prospect of finding out more about Lydia and trying to find out more about the guitar she was playing in the iconic photos of her early career.

Lydia Mendoza was a Mexican-American singer and 12 string guitar player from Houston Texas. She started recording in 1928 with her family band, Cuarteto Carta Blanca, and in 1934 she had a big solo hit with her song “Mal Hombre”. I suggest you give it a listen and read on:

Lydia was a fantastic singer and incredibly inventive and technically proficient 12 sting guitar player. On that front I hold her in the same regard as Leadbelly and Willie McTell. She was a prolific recording artist and performed on border radio stations throughout the 1930s and 40s. She received many accolades for her music and achievements and was recently honored with a U.S. Postal Stamp.

The 12 string guitar that Lydia Mendoza played should not be confused with a bajo sexto. Both have 12 strings, but a bajo sexto is tuned a full octave below a standard six string guitar (like a bass) while Lydia’s 12 string was tuned a fourth below (which is considered a baritone). Interestingly enough, this is the same tuning that Leadbelly and Willie McTell used for their 12 strings. I’ve heard Lydia’s 12 string referred to as a “guitarra doble” and have seen old catalogs where 12 strings were sold as “Mexican 12 strings”.

When Nikki asked me if I would build a copy of Lydia’s 12 string, I told her that it was going to take a while. First I had to figure out what it was, that meant finding out when it was made,who made it, how was it built, how was it tuned etc. That was not an easy task as the guitar world has largely ignored Mexican American instruments and because of that, it was going to be very difficult to find an example to study. I started inquiring with different guitar geeks I know and kept coming up empty handed. Finally the great blues player Steve James, who lives in Austin, Texas and who knows quite a bit about Tejano music, musicians and instruments, told me that he thought that the guitar was made by the Acosta family of San Antonio, Texas. Steve suggested I get in touch with Lydia’s biographer Yolanda Broyles-Gonzalez. Yolanda suggested that I speak with her husband Francisco Gonzalez who was a musician and string maker. Francisco confirmed to me that the guitar was built in the shop of Guadalupe Acosta. He also told me that he had restrung one of Lydia’s guitars at some point. He said she used a standard 12 string set made by D’Addario and that she tuned the guitar down to B. This piece of information was like gold to me. To get confirmation of the builder was huge, but to get an idea of the strings she used and her tuning was a big boost. Neither Steve James nor Francisco Gonzalez knew of anyone with an old Acosta 12 string, but they both told me that the grandson of Guadalupe Acosta, Mike Acosta, had a music store in San Antonio and that I should try to contact him. I found the number for Acosta Music in San Antonio but to my disappointment it had been disconnected.

A friend put me in touch with another San Antonio music store owner, Mark Waldrop. Mark was friends with Mike Acosta and he passed along his number to me. Mike was incredibly gracious and generous with his time and information on his family. Mike ran the Acosta Music Company for 40 years and had only recently retired. He gave me a lot of insight into how his family built guitars and he was a great help in this project. Here is a summary of what he had to say.

Mike’s grandfather Guadalupe Acosta moved to San Antonio Texas from Mexico during the Mexican Revolution, sometime in the 1910’s. He set up shop and worked with his three sons and making a wide variety of stringed instruments. Mike said that in the old days they would make a batch of a dozen six string guitars, followed up by a batch of a dozen 12 string guitars. In the 1950’s the demand for bajo sextos became so great that they spent the bulk of their time making them and didn’t build many six or 12 string guitars. The majority of the guitars had spruce tops and mahogany back and sides, but for the nicer instruments walnut would be used for the back and sides. The earlier guitars were “cross” or ladder braced and later on they used fan bracing for some of their guitars.

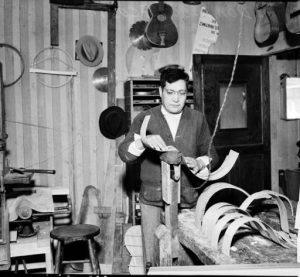

In 1937 a photographer from the San Antonio Light, the local newspaper, visited the shop and took a number of photographs. These photos give an incredible look into an instrument builders workshop at that period in time. They shed much light into the building process, tools used etc. and were invaluable for me during this project.

Guadalupe Acosta sponsored a young Martin Macias when he came up from Mexico. Macias worked in the Acosta shop for eight years or so and then went on to open his own shop. Macias is quite well known for his bajo sextos and his son and grandson followed in his tradition. His grandson George continues to make fine instruments in San Antonio. The old Macias bajo sextos are quite heavy in weight and have stout necks (one of the reasons they are prized by Conjunto players). Mike said that his family’s instruments were built lighter than the Macias’ and had slimmer necks. His father and grandfather felt strongly that the instrument should be comfortable and responsive.

Mike’s father Miguel Acosta grew up in the families guitar shop and remained involved until Guadalupe passed away. Mike had a collection of instruments that his father built and they are all very unique works of art. Mike said that his father really came into his own as a luthier when he returned from service in WWII. The most unique of these instruments is a double neck six string/bajo sexto which is equipped with pickups that his dad built in 1947. Miguel made the guitar for himself to play at gigs where he was required to play both six string guitar and bajo sexto. Mike’s son pointed out to me that this is probably the first double neck electric guitar ever made and that his grandfather should have applied for a patent.

There was also an 18 string guitar which has a very unique shape (you can see an 18 string neck on the workbench in the above 1937 photo of Miguel). This would have had six courses, with three strings in each course. Mike told me about a guitar that his father made to look like a lava lamp, “It’s hard to describe.You just have to see it.”

I was really blown away with the work that the Acosta family had done. Their instruments were so creative and beautiful, I couldn’t believe that I hadn’t heard of them before and that they weren’t more widely recognized. I came away from the conversation energized and feeling prepared to get to work.

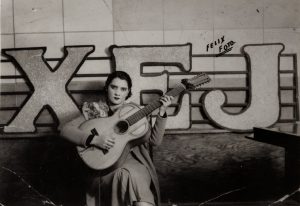

Have I mentioned that I still hadn’t been able to find an example of a 12 string made by the Acosta family? I did find out that Lydia’s had been stolen from her at some point and there was no hope of tracking it down and using it for reference. I did have though the information that Mike had given me and a photo of his father building a 12 string which offered many clues. I needed some good photos of Lydia with the guitar. I contacted the Arhoolie Foundation which has done an incredible job of preserving Lydia’s music, and they graciously shared photos of Lydia with the guitar which I have included here. Each photo gives a glimpse into different details of the guitar, the woods used, the trims, the dimensions etc.

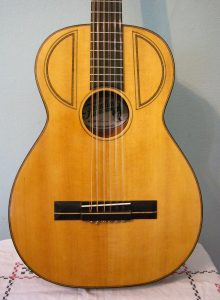

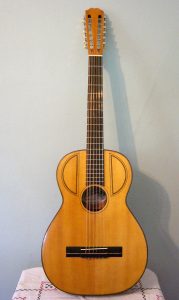

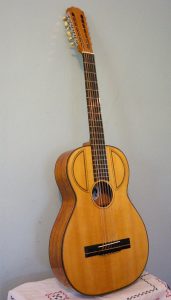

I spent several weeks pouring over all the information, organizing the photos chronologically, making notes on the details and then making scale drawings based on the photographs. I made over a dozen plans before I came up with one that I was happy with. The final plan had a scale length of 26 1/2″ and a lower bout of 14 1/4″. Of course I can’t be sure that it is perfect, but I’m confident it comes close. I would love more than anyone if someone could produce an Acosta 12 string that was built around the same time as Lydia’s to see how right or wrong I was. I can only hope that it happens.

Judging from the information that Mike Acosta had given me, as well as the way that the light reflects off the guitar in black and white photos, I decided to use mahogany for the back, sides and neck, and spruce for the top. I chose ebony for the fingerboard and bridge.

Inlaying the D shaped inlays on either side of the fingerboard proved to be a challenge. I have a router with holes in the base which operates like a compass, but normally I drill a hole through the top of the guitar to create a pivot point, as is the case with the soundhole and rosette. With the D inlays, I was unable to drill through the top of the guitar and into a workboard, so I had to make a template which I could clamp to the top of the guitar, which had a pivot point as well as the D cutout. It worked pretty well. Getting the D holes to line up symmetrically with the fingerboard, rosette and edge purfling was quite difficult and I did manage to lose one top in the mix.

Inlaying the D shaped inlays on either side of the fingerboard proved to be a challenge. I have a router with holes in the base which operates like a compass, but normally I drill a hole through the top of the guitar to create a pivot point, as is the case with the soundhole and rosette. With the D inlays, I was unable to drill through the top of the guitar and into a workboard, so I had to make a template which I could clamp to the top of the guitar, which had a pivot point as well as the D cutout. It worked pretty well. Getting the D holes to line up symmetrically with the fingerboard, rosette and edge purfling was quite difficult and I did manage to lose one top in the mix.

The bridge was another piece of the guitar that was quite distinct. I noticed in the photos of Lydia with the guitar that there was a strip of white wood that was running through the bridge at a certain point. In all the photos her hand is covering up the middle of the bridge, so I was unable to make out the specific details. I came to the conclusion that it was a laminated bridge, ebony or some sort of “ebonized” wood, with a piece of maple running through the top of the tie block. I think this design was to give strength to the ebony at the tie block as there are 12 small holes going through that portion of the bridge and quite a bit of string pressure being exerted on the weakened wood. It seems that eventually that part of the bridge would split due to all of the work it was required to do.

Another thing that is noticeable from the photos of Lydia is the metal tailpiece. In the old days, people didn’t always think to repair guitars, at least not to the extent that they do today. Oftentimes the repair for an unglued or failed bridge was to put a metal tailpiece on a guitar and transfer the string tension from the bridge to the tailpiece. In the early photos of Lydia and her mother with the guitar (from c1928 to 1934) there is no tailpiece. The tailpiece shows up in the later 1930’s, I suspect that the bridge finally failed at the tie block and the tailpiece was the solution. I did tell my friend Nikki that if the bridge failed, I’d happily make her a tailpiece as a solution (if she didn’t want the bridge replaced).

Another thing that is noticeable from the photos of Lydia is the metal tailpiece. In the old days, people didn’t always think to repair guitars, at least not to the extent that they do today. Oftentimes the repair for an unglued or failed bridge was to put a metal tailpiece on a guitar and transfer the string tension from the bridge to the tailpiece. In the early photos of Lydia and her mother with the guitar (from c1928 to 1934) there is no tailpiece. The tailpiece shows up in the later 1930’s, I suspect that the bridge finally failed at the tie block and the tailpiece was the solution. I did tell my friend Nikki that if the bridge failed, I’d happily make her a tailpiece as a solution (if she didn’t want the bridge replaced).

The shape of the headstock is something which also seems to have changed over time. In the oldest photo of the guitar, the one in which her mother is playing it, the profile of the headstock seems very strong and distinct. The headstock of the guitar Miguel Acosta is building in the photo has a very similar shape. In later years the headstock seems to have been cut down a bit and the profile is not as sharp. My only thought here, and this is speaking from experience, is that at a certain point Lydia needed a case for the guitar. It is very difficult to find a case for a small bodied, long scaled guitar with a long headstock. Cases that fit the body won’t accommodate the overall length of the guitar and cases which fit the length don’t offer much protection for the body because they are too big and the body bounces around. In order to get the guitar to fit into a case that fit the body properly, some material had to be removed from the top of the headstock. I have seen this in at least one other case (no pun intended)

I’m very happy with the way that the guitar turned out. It was very light in weight and responsive. It was a great joy for me to build it for Nikki who will do it, and Lydia’s music, justice. I thank her for giving me the opportunity to build it and to delve into this world. It was great to speak with Mike Acosta and his son Mike. Many thanks to them for being so generous with information and for providing photos of the instruments that Miguel Acosta had built. I hope that this project brings some more recognition to the wonderful work that their family did and that they are recognized as the great American luthiers that they were. Maybe then more of their instruments will be flushed out of the woodwork. Thanks to the Arhoolie foundation for the loan of the photos of Lydia with the guitar. Thank you to Yolanda Broyles-Gonzalez, and to Francisco Gonzalez for the information on Lydia’s strings and tunings.

I’m very happy with the way that the guitar turned out. It was very light in weight and responsive. It was a great joy for me to build it for Nikki who will do it, and Lydia’s music, justice. I thank her for giving me the opportunity to build it and to delve into this world. It was great to speak with Mike Acosta and his son Mike. Many thanks to them for being so generous with information and for providing photos of the instruments that Miguel Acosta had built. I hope that this project brings some more recognition to the wonderful work that their family did and that they are recognized as the great American luthiers that they were. Maybe then more of their instruments will be flushed out of the woodwork. Thanks to the Arhoolie foundation for the loan of the photos of Lydia with the guitar. Thank you to Yolanda Broyles-Gonzalez, and to Francisco Gonzalez for the information on Lydia’s strings and tunings.

If you’re interested in learning more about Lydia Mendoza, I highly recommend checking out some of her music on the Arhoolie Record label. They have recordings she made throughout her career. She also appears in the1979 Les Blank film “Chulas Fronteras“, which is a great look into Tejano music. For an in depth look at her life, I recommend her biography “Lydia Mendoza’s Life in Music / La Historia de Lydia Mendoza” by Yolanda Broyles-Gonzalez.

You can read more about the Acosta family in “Hecho en Tejas: Texas-Mexican Folk Arts and Crafts”, which features an interview of Miguel Acosta and outlines his construction of a bajo sexto. The Acosta family is also featured in the book “The Mexican-American Family Album” by Dorothy an Thomas Hoobler.

Todd Cambio

June 2014

Postscript. Here are a couple clips of Nikki Grossman playing some Lydia Mendoza tunes on her 12 string. This was such a great project! Not only did I get to delve into the world of Lydia Mendoza and the Acosta family, I was able to make an instrument for a great friend and fantastic player.

11 Comments

Beautiful, Todd.

Thanks Geoff. It was a very fun project for me.

astonishing work!

Thanks for the post. Beautiful guitar!!

Thanks for sharing your awesome research into the guitar and for the introduction to Sra. Mendoza's music!

I love this article — what a lot of research! We are publishing an eBook for children about Lydia Mendoza and would like to include some of the photos you used and especially, a photo of her guitar. Can you help? miranda.barry@fablelearning.com

Wow great work i love lydia

Mr. Cambio you mentioned a person name Francisco Gonzalez do you a contact number for him . I would like to get in touch with him . thanks

My friend Mike ramirez has a 12 string guitar inside it G Acosta is the name in it its in good shape it was his dads who was in a band and they lived in Texas back then he’s selling it but he dont know what its worth and wants to find out ?

This is a heavy hitting inspirational phenomenal piece of story and work. Wow!!!

Thanks Hannah.