Lonnie Johnson’s Mysterious 12 String

Decalomania 6 and 12

January 18, 2017

The Black Hole

May 18, 2018My creative spirit feeds off of unusual sounds and images. I love to try and figure out what kinds of instruments made the sounds on old records and what musicians were photographed with. The more unusual the instrument and its sound the better. I am especially fascinated by the instruments that came from small, independent shops. I have puzzled over country music pioneer Ernest Stoneman’s Galiano, Willie McTell’s Tonk Brothers 12 string, and Lydia Mendoza’s Acosta 12 string. I have eventually made copies of each of those instruments. In the best case scenarios I’ve had an instrument to use as a reference. In the case of Lydia Mendoza’s 12 string, I worked with a half dozen photos and interviewed the grandson of the maker to piece together the details for a working plan. Over the years the greatest mystery for me has been the 12 string that the dapper young Lonnie Johnson was photographed with, in one of the most iconic of all blues images. Unlike Lydia’s guitar, which had several photos from several angles, there is only a single photo of Lonnie with his 12. It’s difficult to make out details of the guitar as it is overexposed. The bridge is very distinct. There is something unusual going on with the headstock, but I had never been able to figure it out. It’s impossible to make out the details of the purfling. I had read that Lonnie had the guitar custom made in Mexico. I’ve always wanted to know where that theory originated? Who was the maker? What were the particulars? Eventually my curiosity and obsession got the best of me and I had to put the nose to the grindstone to figure it out.

Lonnie Johnson was born to a musical family in New Orleans in 1899. He studied several instruments starting at a young age, eventually settling on guitar. His recording career started in 1925 after winning a contest for Okeh records. In general he was pigeon holed as a blues guitarist, though his range extended beyond blues. He became one of Okeh’s best selling artists with his solo recordings and backing artists like Texas Alexander and Victoria Spivey. In 1929 he made some ground breaking records with jazz guitar pioneer Eddie Lang who used the pseudonym “Blind Willie Dunn” for the sessions as it was not yet socially acceptable for black and white musicians to record together. These days it seems that Lonnie Johnson is overlooked. Blues aficionados tend to appreciate players with a harder edge, and jazz fans don’t seem to pay him much mind. Nevertheless Johnson was an incredible, prolific player who was extremely influential for early jazz and blues guitar players. At the time he was one of the few blues players to play single note leads and frequently bend notes. You can hear echoes of his playing in T-Bone Walker, Charlie Christian, and with later players like B.B King. Even in the duets with Eddie Lang, it’s Lonnie who seems to be featured, and when Lang steps up for a solo, it sounds like he’s playing Lonnie’s licks.

The 12 string added an ethereal quality to Lonnie’s playing. an airiness as he floats over and around the rhythm. It’s a completely different sound from other 12 strings of the era. Lonnie didn’t tune the 12 string as far down as Willie McTell and Leadbelly, both of whom treated it like a baritone instrument. He also didn’t string it with all 12 strings. In the photo he has 10 strings, the first two courses are single strings, while the others are doubled. On most of the recordings it sounds like a 9 string with the first three courses doubled, and the three lower strings are singles. All the doubled strings are tuned in unison and no octave courses are audible. He likely used this arrangement so as to not muddy up his sound, to focus on the crispness of the treble strings. On a few recordings it sounds like the guitar is strung with all 12. You can hear doubled strings as he solos on the bass strings or plays rhythm. As a guitar maker, I kept coming back to the question, what in the world was that guitar?

The photo of Lonnie with the 12 is on the cover of the marvelous book “Nothin But the Blues” by Larry Cohn, which was first published in 1993. That was really when I first became aware of the guitar. I had heard that Larry Cohn knew who had made the guitar so I dropped him a line. He was very gracious with his time and he told me that in the 1960’s Mack McCormick had told him that a luthier in Mexico had made Lonnie’s 12. He did not remember the name of the luthier and was not able to find the letter which Mack had written him. Now I knew the origin of the theory that Lonnie had the guitar made in Mexico, but I wanted to know who made it and what it was.

At one time the baritone 12 string, or guitarra doble, was incredibly popular in Mexican music and in Mexican string orchestras. There were many small shops in Mexico that made 12 strings, and large US factories like Oscar Schmidt made “Mexican 12 strings”. Mike Acosta told me that his grandfather’s shop in San Antonio would make a dozen 12 strings followed by a dozen six strings. The bajo sexto (bass 12 string) came onto the scene in the 1930’s, eventually becoming so popular that it outstripped the demand for the baritone 12 string. By the 1950’s all the Acostas were making were bajo sextos. Very little, if anything, is known about these smaller Mexican shops and their instruments. These days they are incredibly rare. In years of looking for old 12 strings, I have only seen two made in Mexico. Both bore some resemblance to Lonnie’s 12, but his was still very distinct.

|

| Lydia Mendoza in the studio in 1936, photo from the Arhoolie Foundation. |

After I made a copy of Lydia Mendoza’s 12 string and wrote about the Acosta family who had made her guitar, a few friends asked me if I thought that the Acostas had made Lonnie’s guitar? Initially I considered it a possibility but I needed some proof. Then a friend, Joe Brennen, sent me a quote from a 1960 interview of Lonnie Johnson by Paul Oliver, ” I bought that 12 string guitar in San Antonio…….They only make 12 string guitars in San Antonio. The Mexicans and Spanish that’s all they use…” That changed everything! Here are the words of the man himself saying that he got the guitar in San Antonio, Texas, and that it was made there. There was only one shop in San Antonio making and selling 12 strings at the time, The Acosta Music Company.

I immediately started measuring the guitar in the photo and comparing it with the dimensions of Lydia’s guitar. After I had established a ratio for Lonnie’s 12, I realized that it was nearly identical to Lydia’s, with one big exception, Lonnie’s guitar had a shorter scale. Lydia’s guitar had a long 26 1/2″ scale, while Lonnie’s had a shorter 24 7/8″ scale. This shorter scale was unusual for a 12 string at that time, but would explain their difference in tuning. Lydia tuned down 2 1/2 steps to B, while Lonnie only tuned to pitch, or down a step to D. To the layperson the difference in scales would seem very unusual, but as a luthier I realized that if you cut a 26 1/2″ fingerboard at the first fret, you get a 24 7/8″ scale. It’s an old trick used by many shops, small and large, allowing you to make several different instruments with a single fingerboard template (people use capos to achieve this same effect). It was beginning to look like the Acostas were the makers of Lonnie’s guitar. A few more details were coming that would cinch the deal.

|

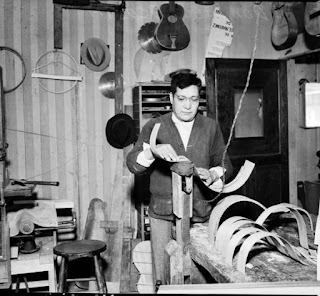

| Guadalupe Acosta bending sides in 1937 from the San Antonio Light Collection. |

Guadalupe Acosta was born into a family of luthiers in Lagos di Moreno, Jalisco, Mexico. He built instruments with his father and brothers and would eventually pass the craft onto some of his sons. He had six children, Domingo, Luis, Francisco Cuca, Miguel, Jesus and Jimmy. In 1915, during the Mexican Revolution, Guadalupe moved his family north to Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, which is on the border with Texas. Guadalupe went on to San Antonio, Texas to work as an instrument maker under Teodoro Navarro. In 1920 his family moved from Nuevo Laredo to join him in San Antonio. That same year he opened the Acosta Music Company in San Antonio. He sold instruments that he made at the store and eventually his sons Luis, Miguel and Jesus came to join him in the business.

Another interesting piece of information came to light, listening to a 1973 interview with Luis Acosta by Chris Strachwitz. As the Acosta Music Company began to grow , Guadalupe was contacted by record companies and asked if he would recommend talent from San Antonio for field recordings that were to be done there. These types of field recordings started at Okeh Records in 1923, in order to capture types of music which were not available in the New York area. It was common practice for the record companies to ask dealers of their records or phonographs to act as A&R men. H.C. Speir played this role for blues players in Mississippi, Guadalupe and Luis Acosta did for Tejano talent in San Antonio.

Right around this time I had the good fortune to spend a weekend with the great American music historian, record collector and author of the discography Ethnic Music on Records, Dick Spottswood. I ran the theory past Dick, that the Acostas had made Lonnie Johnson’s 12 string, and he had a brilliant reply that only a discographer would think of. He told me to look at Johnson’s discography, find out if and when he recorded in San Antonio, then look at the first time he recorded with the 12 string and compare the dates

|

| The Mendoza family circa 1930. |

As it turns out, the first field recording to be done in San Antonio was by Okeh, at the Plaza Hotel, from March 3rd to 14, 1928. Among the artists there were Lonnie Johnson and the Mendoza family’s Cuarteto Carta Blanca, as well as other Mexican musicians whom the Acosta’s had recommended. Lonnie recorded solo and with Texas Alexander on the 9th and 10th, then again on the 13th. The Mendoza family recorded on the 10th. I don’t know if Lydia’s family had her Acosta 12 string yet, but Lonnie was bound to have some contact with a 12 string while waiting around the Plaza Hotel, and with a few days to kill between sessions, with recording money in his pocket, he was bound to end up at the Acosta Music Company.

Figuring out when Lonnie first recorded with the 12 was a bit tougher as distinctions like this aren’t in discographies. I had to listen to recordings and enlist the help of a few friends with good ears (Chris Berry, Allan Jones and Frank Basile). You can hear vague hints of something that sounds like double courses in a passing phrase on some of Lonnie’s early records, but the first session that you can definitively hear the 12 is on November of 1928 in New York, seven months after his San Antonio sessions.

I return to Lonnie’s quote:

” I bought that 12 string guitar in San Antonio…….They only make 12 string guitars in San Antonio. The Mexicans and Spanish that’s all they use…”

Now I was relatively certain that it was the Acostas who had made Lonnie’s 12. I was ready to start trying to figure out the details in order to make a copy. Because there is only a single photo and as the details of the guitar are hard to make out, it may be more accurate to say that I was going to make my interpretation of he guitar in the photo. I was going to have to rely on clues from other research I’d done on the Acosta’s, and on Lydia Mendoza’s 12 string. For starters, what was going on with the headstock? There’s some sort of unusual veneer, but what?

When I was researching Lydia’s 12, I interviewed Mike Acosta, son of Miguel and grandson to Guadalupe. Mike had grown up around the family shop and eventually opened his own music store in San Antonio, which he ran for a number of years. Because Mike was in the business, he was very knowledgeable about how his family built instruments, the woods they used, the way they braced them, the types of instruments they built. Mike told me that his uncle Luis (whom Chris Strachwitz interviewed) had once built a guitar out of tiny squares of wood. He said it was a very unusual thing and hard to explain. When I asked him what happened to the guitar he said that it had fallen apart but that he still had a piece of it.

|

| Luis Acosta with his striped guitar, 1940, San Antonio Light Collection |

In a 1940 photo from the newspaper, The San Antonio Light, Luis has a guitar which he made out of strips of wood. The caption reads, “(Luis) spent six hard weeks fitting the tiny pieces into a well toned instrument. He didn’t make it to sell; he just made it for the heck of it. Woods include black walnut, cottonwood, spruce and mahogany.”

I turned this bit of information toward Lonnie’s 12. Could something like this be going on with his headstock? I found a high resolution copy of the photo and went to work. With a jeweler’s loop I could see that there was a checker pattern going on in the headstock. I could actually count the rows of checkers and divide them by the overall measurements of the headstock in order to figure out their size. I started to wonder how Luis may have done this.

It wasn’t a straight checker. There was more light space than dark. My friend Taylor Rushing said it reminded him of the number five on a pair of dice. I started gluing and slicing pieces of maple and ebony and playing with the patterns. I went through a few iterations before I came up with something that I was happy with and that made sense.

I could see that at the bottom of the tuner slots the checker pattern turned to black. Under magnification you can see a visible ledge where the veneer stops. My only explanation was that the veneer suffered the same fate as Luis’ checkered guitar and had started to fall off between the time the guitar was made and the photo was taken. Lonnie presumably got the guitar in San Antonio in the spring of 1928 , where it would have been hot and humid. Then he took it to New York, where he recorded in the summer and fall. Had he stayed in New York, the temperature would have dropped as well as the humidity. The guitar was bound to have had a tough time adjusting to the change.

You can also tell from the photo that the headstock is an odd shape. There is a radius across the top and the portion above the tuners is slightly wider, so that the tuners are inset. There also appear to be some notches across the arch of the top. I made a few drawings of the head before I came up with something I was happy with.

In coming up with the shape for the guitar I was somewhat limited as the guitar is at a slight angle in the photo. From my best estimations after developing a ratio for measuring the guitar, the dimensions of the body were identical to Lydia’s. The length of the body, the width of the upper and lower bouts and the waist, where the curves fell in relationship to the body length, all things were equal. I decided to use the form I had come up with for Lydia’s guitar rather than make a new one. Lydia’s guitar may be slightly curvier than Lonnie’s but it is very close. I am very confident of the dimensions.

| Fraulini Lonnie Johnson 12 string |

It’s difficult to tell what types of woods were used in the photo. The top is obviously spruce. The sides are dark. I was again reminded of something Mike Acosta told me when I asked about what types of woods they would use. Mike said that they used mahogany for almost everything, except for the good stuff, for which they would use walnut. I thought that the side wood looked too dark to be mahogany, and because this was the good stuff, I went with walnut. The fingerboard and bridge are black and shiny and appear to be ebony, so that is what I used for the fingerboard and bridge. The neck is magnolia. I know that was a popular wood for bajo sexto makers in San Antonio and I liked the contrast with the back and sides. It fit the checker pattern nicely.

One of the very distinct features of the guitar is the bridge. It is a wide but squat pyramid with six offset pins. The strings that are doubled share a pin hole. This is a fairly unusual arrangement. Because Lonnie’s sound is so light and airy, and because a large part of that sound is his bending of notes, I went with light strings with the action on the high side. The strings range from .010″ to .050″. The three treble strings are doubled, while the three bass strings are singles.

It’s impossible to make out the details of the purfling and rosette. You can tell where the lines fall, but not what the lines are. They appear to be straight lines rather than a mosaic pattern. Here too I deferred to Lydia’s guitar for which I could make out the details from the various photos. I went with a simple black/white/black line.

This project was extremely enjoyable for me. It has spanned many years and has presented many cross disciplinary challenges. I’m fairly confident that it was Guadalupe Acosta and his son(s) who made Lonnie Johnson’s 12 string. That alone is a beautiful thing that is uniquely American. An African American jazz and blues pioneer from New Orleans playing a guitar made by a Mexican immigrant and his sons, picked up in a small shop during a remote recording session in San Antonio. Then he took it to New York to make some seminal recordings with an Italian American from Philadelphia. If a safe, piano, or heaven forbid an elephant should fall from the sky tomorrow and send me to the other side, I could rest contented that I have completed this project.

I’m fairly confident that I came close to the mark on my copy. As with all these types of projects, I would be thrilled if the original came to light and I could see how close or far I came. The true test is the sound. For that I am not qualified, so I sent it to some friends who were. Here’s Ari Eisinger and Frank Basile playing the Lonnie Johnson and Eddie Lang duet, Bullfrog Moan:

You can find out more about Ari Eisinger at secondmind.com. Frank Basile here.

13 Comments

Hi, very interesting story. There´s one detail that strikes me as odd: Guadalupe is a woman´s name in spanish, not a male name, and you refer to Guadalupe as a “he”. Might not be significant, but as a spanish speaker it inmediately caught my attention.

Thanks for sharing the story.

Thank you. I can assure you that the man’s name was Guadalupe Acosta. His labels read, ““Guadalupe Acosta,” Fabricantes de Toda Clase de Instrumentos de Cuerda y Encordadura. 608 W. Houston St., San Antonio, 7, Texas.” I have seen photos of him in old newspapers and I have spoken with his grandson. It may be an unusual name for a man, but it was his name.

You need to study your history. Guadalupe is a very common name for Male gender also.

Well, I did some Googling and it turns out that Guadalupe is BOTH a a female and a male name. I live in Argentina and here I´ve never heard the name applied to a male, that´s why It called my attention, possibly in Mexico it´s more common practice. Live and learn.

Again, thanks for sharing your research and beautiful guitars, by the way!

Cheers

Saint Guadalupe is the patron saint of Mexico. The name Guadalupe is used by both men and women in Mexico.

According to the article, Lonnie Johnson’s first session with the 12 string was in November 1928, however my ears tell me he plays the 12 string on two sessions for OKeh from the previous month:

October 1, 1928 Duke Ellington and His Orchestra/Lonnie Johnson’s Harlem Footwarmers*: The Mooche, Move Over*, Hot and Bothered.

October 13, 1928: The Chocolate Dandies: Paducah, Star Dust.

All of these tracks can be heard on YouTube.

Thanks for the feedback. I really appreciate it. I have to admit that I was not aware of the extent to which Lonnie recorded Jazz. I know more about Blues history than Jazz. When I was trying to figure out when his first session with the 12 was, I only explored his Blues recordings. After I wrote this article and finished this project, a few people hipped me to his recordings with Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. It’s my oversight. The realization that he made significant contributions to the Jazz world increase the depth of my appreciation for him as a player.

Interesting read and I love the guitar. I wouldn’t mind seeing what you come up with building a replica of Django Reinhardt’s Gypsy Jazz Grande Bouche with resonator?

Hello, Lagos de Moreno, not “di” for the Acosta families roots! I live in Guadalajara and go to Lagos de Moreno pretty often. “Di” would be Italian for sure!

I’d love to see if the family is still around there! I’ve got my ’20’s Oscar Schmidt Stella killing it down here in Guadalajara!

Aye Caramba! Sorry about that, I should know better. Italian creeps into my Spanish, but not as much as Spanish creeps into my Italian, so much so that I have my own dialect.

!Por Dios y todos los santos! I speak a little Spanish, French, English, & Hawaiian. Yes, the Hawaiians have their own language…. I get ’em all mixed up. Lonnie Johnson, Django, Charlie Christian, Leonard Kwan, & Gabby Pahinui are all my idols. Miguel/Mike/Mika’ele McClellan.

Have you read the Acosta/Johnson material in “Blues Comes to Texas”? Might be of interest (48 strings!?!)

I have. Paul Oliver’s interview with Lonnie Johnson is great. I think Mac McCormack interviewed Luis Acosta. I wasn’t crazy about that part. I’ve done a lot of work with the Acosta family, worked on some of their instruments and done a lot of research over the past few years. I’ve been writing about that as well as some of my other work. I hope to have something presentable in a year or so.